It seems that, in the public’s perception, scientists are a secretive bunch. As a scientist, I know that is not the case. Communicating ideas and findings to others is an indispensable part of doing science and, especially when overcome by the thrill of discovery, scientists are not very good at keeping secrets.

Each gravitational wave detection by the LIGO-Virgo collaboration is kept secret for months while the discovery is carefully analysed, vetted, and then written up for publication. This is done to ensure that premature findings and analyses don’t muddy the waters, and that the scientists who made the discovery get to reap the rewards of their work, without getting scooped by others. But science does not play well with secrecy, especially when thousands of researchers from dozens of countries are involved. If you know what you’re looking for, the science is there to be found.

For me, the first hints of a new gravitational wave discovery came from the behaviour of the gravitational waves physicists in the building I work in. They didn’t turn up to morning tea, and for days muffled meetings and teleconferences could be heard behind the closed doors of their offices. I could tell there was frantic activity going on, just not what that activity was.

This had happened several times before, and I knew they must have made a new and exciting detection.

Then the rumours started.

It started on social media. A tweet, which was later deleted, was doing the rounds amongst physicists on twitter. It said:

It sounded like they had seen a gravitational wave which also gave off a visible explosion. That is awesome news, but I was sceptical. Previous detections had been accompanied by similar tweets that had turned out to be wrong. Could this one be trusted?

Then people started to notice where the telescopes were pointing.

Many telescopes and observatories are publicly funded, and are required to tell the public what they are doing and what they are looking at, even if they don’t actually show the public the images they’d taken.

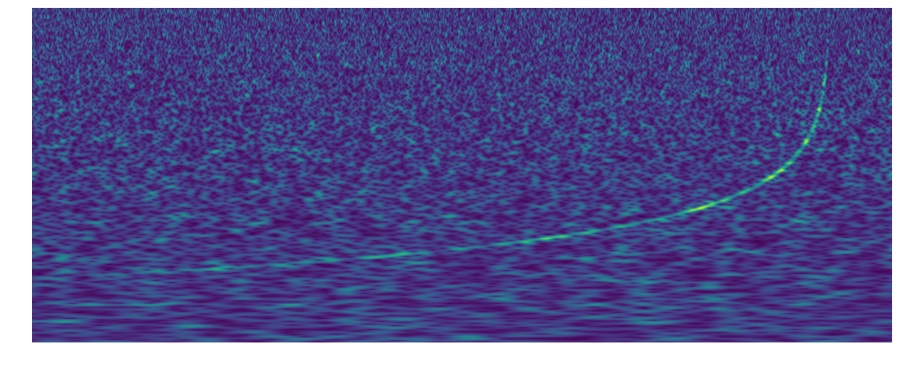

For several days following the rumoured gravitational wave detection, telescopes around the world including the Hubble, Chandra, ALMA, VLA and ATCA were all found to be pointing at the same patch of sky. There were reports that other projects going on at these telescopes had been cut short by a priority interrupt. They were all pointing at a galaxy known only by its catalogue designation NGC 4993.

So I Googled NGC 4993, and was surprised to find that it had its own Wikipedia page.

The Wikipedia page for NGC 4993 reported that NASA’s Fermi satellite had detected a short gamma ray burst, catalogued as GRB 170817A, from the galaxy, and that it was rumoured that the gamma ray burst coincided with an as yet undisclosed gravitational wave event. The dates certainly matched.

Astrophysicists had long speculated that short gamma ray bursts were caused by the collision of two neutron stars, an event that LIGO is expressly designed to detect. If these events were connected, this was big news. This would be the first time a cosmic event had been observed by both telescopes and gravitational wave detectors. It would have provided huge quantities of unprecedented data, and answered questions about neutrons stars and gamma ray bursts that had been debated for half a century.

I had enough evidence for now. Next, I confronted the gravitational waves people.

Although they were busy checking calculations and writing papers, they still had to emerge from their offices now and then to teach class.

“So, when is the neutron star merger being announced?” I asked.

Often they would respond, “Who told you?” But just as often, they didn’t know I wasn’t a gravitational waves physicist from a different group, and they would spill the beans.

I found out that, purely by luck, I was due to be in Canberra on the day of the announcement, not far from where the Australian press conference was being held. If I could sneak in to the conference, I would get to celebrate this momentous discovery along with the scientists who had made it possible. I do own a t-shirt with a gravitational wave pattern on it, I decided I’d better wear that to the press conference, it might make me look like I’m meant to be there.

It turned out that sneaking in was the easy part. The scientists wanted to share their discovery with the world, and would welcome as many people as the venue would hold. I got to hear the story of the discovery first-hand, and watched as dozens of physicists and astronomers celebrated the dawn of a new era in astronomy, the use of gravitational waves and light, in combination, to study the universe in greater detail than has ever been possible before.